WELCOME TO THE ANTHROPOCENE?

- Oct 26, 2017

- 4 min read

Goodbye Holocene, hello Anthropocene. Let’s give a warm welcome then. And we sure did in 2016, the hottest year on record, the 4th hottest in North Australia (Bureau of Meteorology). The Anthropocene, or the ‘age of humans’, is a proposed geological epoch that, in theory, reflects human impact on the Earth. As the US is now pulling out of the Paris climate agreement of 2015, things will get warmer. They certainly will politically, and the naming of ‘The Anthropocene’ is a growing part of this debate, as it is recognition that we as a species, like microbes started 3 billion years ago, are ‘terra-forming’ the planet.

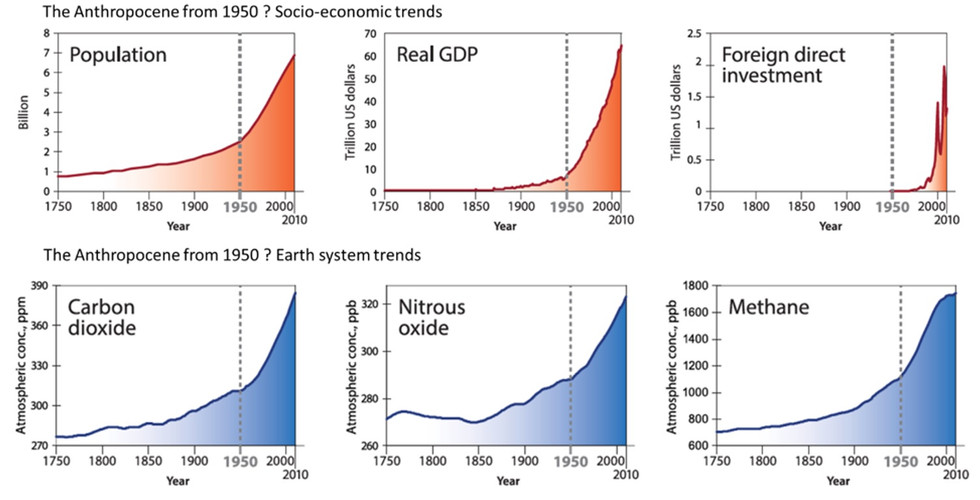

Our current epoch (the Anthropocene hasn’t officially been accepted yet), the Holocene, is around 11,700 years old and is considered a climatically stable, warm, interglacial phase of the current ice age, a period of rapid growth and expansion of the human species. This epoch has now ended, according to the anthropocenists, via the Working Group on the Anthropocene (WGA), a 35-strong panel that has been in deliberations for 7 years on the existence of this epoch. As of August 2016, the WGAs decided the Holocene has ended, with the start of the Anthropocene beginning in 1950, the period of the ‘Great Acceleration’ where the Earth’s population growth, consumption and earth system indicators exceeded the natural variability of the Holocene (Figure 1). However, the WGA’s submission has yet to be ratified by the International Commission Stratigraphy (ICS), a body of the International Union of Geological Sciences (IUGS) which precisely defines the series and stages of the International Chronostratigraphic Chart, i.e. the duration of geological units that define the history of the Earth.

The concept, the name and its utility is hotly contested, even by those who accept the term, the ‘anthropocenists’. They argue over the actual date, or period where we can see distinct change to the Earth’s systems over and above natural variability of the previous geological epoch, the Holocene. Others question the need for such a term, or question the lack of engagement with social sciences when shaping the concept and deciding the epoch’s beginning. Scourse (2016), writing in The Conversation, suggests that the concept has;

“… stimulated a redundant, manufactured, debate that displaces more important scientific research and genuine discussion on climate and environmental change. It is a fad, a bandwagon, a way of marketing research as cutting-edge and relevant. At its worst it can be seen as a disingenuous means of harvesting citations under the guise of serious endeavour.”

So the suggestion here is that the concept is largely pop-science, we know enough already, and we don’t need a 3 year study and lengthy debates to determine that we are in a new era. We need to get on with re-engineering our economy, governance, natural resource management and wealth distribution etc. Ellis suggest the opposite – that the process and debate is happening too fast and that a more considered, transparent approach that is far more inclusive and captures perspective from social sciences; anthropology, archaeology, history, sociology, geography, palaeoecology, economics and philosophy is required. Of the 37 WGA expert panel members, only three are social scientists, yet the fundamental characteristic of the Anthropocene, is purportedly due to the evolution and action of human societies. Involvement of the social sciences would better determine why, as well as how, human activity is impacting the planet and help define a new ‘age of humans’ from more than a Western-scientific perspective on its own.

As these are geological eras, for an epoch to be declared, significant changes to the atmosphere, hydrosphere, biosphere, and lithosphere must be reflected in the stratigraphy, or rock strata. Is this possible in 200 years of industrialisation? Should the boundary be marked in the 1600s, when agriculture rapidly expanded, shifting atmospheric chemistry, and began a process of population growth, habitat destruction and species loss, alteration of streamflow and sedimentation dynamics? The 1950s is of a human lifespan, and such a marker relegates thousands of years of human impact and considerable anthropogenic change to a “pre-Anthropocene”. Change has been underway at varying rates for the last 10,000 years.

In short, many geologists and social scientists are not all on-board, as the concept has been driven by the Earth system and climate scientists. Is this a useful term, is there a definable epoch boundary? Recent sedimentological analysis suggests that there is, and that we are seeing a geological foot-print in both sediment and ice cores that is distinct in nature from the Holocene, a critical component of any acceptance of the Anthropocene era by the ICS. A UK team lead by Colin Waters assessed sediment cores drilled in the west Greenland ice sheet and found ‘novel materials’ and ‘technofossils’, waste products from the technological age including plastic particles, aluminium, concrete, polychlorinated biphenyls and pesticide residues, and fertiliser residues. Such materials were not easily detectable in sediments laid down prior to the 1950s. Glacial retreat also resulted in an abrupt stratigraphic transition from proglacial sediments to non-glacial organic matter, an important marker.

Given this geological footprint, contemporary rates of extinctions up to a hundred times the background (pre-human) extinction rate, well documented socio-economic changes , earth system climate variables (Figure 1), and the recent submission from the WGA, there is a case to be made. Perhaps we are seeing the beginnings of Anthropogenic-like environmental change in our region with mass bleaching of coral reefs in 2016 and again in early 2017, and even the globally unprecedented mangrove dieback that stretches 1000 km across the Gulf of Carpentaria coastline (Figure 2). These events are very likely due to a combination of climatic factors resulting in lethal environmental conditions, ‘tipping’ these ecosystems to a different state.

Clearly an intervention from the social sciences is needed, even though this is a geological framework. The nature of an Anthropocene changes this given the direct human causality a rigorous definition will arise, as well as use and promulgation of the terminology across more disciplines.

Professor Lindsay Hutley is a plant physiologist with RIEL at CDU.

Comments